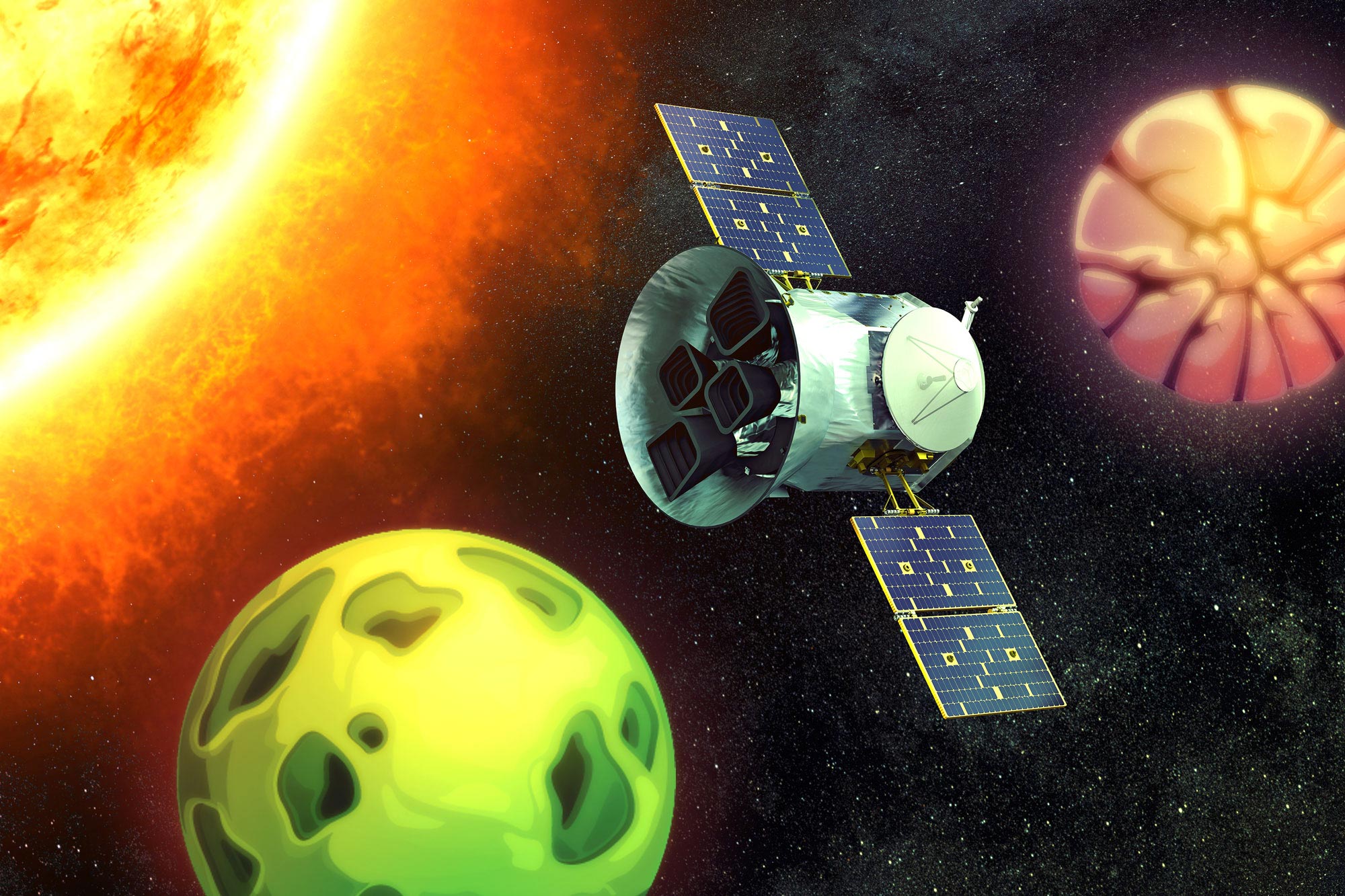

Gli astronomi del MIT hanno scoperto un nuovo sistema multirete situato a 10 parsec, o circa 33 anni luce, dalla Terra, rendendolo uno dei sistemi multirete più vicini al nostro sistema. La stella al centro del sistema probabilmente ospita almeno due pianeti terrestri delle dimensioni della Terra. Credito: MIT News, con carattere TESS Satellite per gentile concessione della NASA

Situato a soli 33 anni luce dalla Terra, il sistema sembra ospitare due pianeti rocciosi delle dimensioni della Terra.

Un nuovo sistema multiplanetario è stato scoperto all’interno della nostra galassia vicina dagli astronomi di[{” attribute=””>MIT and elsewhere. It lies just 10 parsecs, or about 33 light-years, from Earth, making it one of the closest known multiplanet systems to our own.

At the heart of the system lies a small and cool M-dwarf star, named HD 260655, and astronomers have found that it hosts at least two terrestrial, Earth-sized planets. The rocky worlds have relatively tight orbits, exposing the planets to temperatures that are too high to sustain liquid surface water. Therefore, they are unlikely to be habitable.

Nevertheless, scientists are excited about this system because the proximity and brightness of its star will give them a closer look at the properties of the planets and signs of any atmosphere they might hold.

“Both planets in this system are each considered among the best targets for atmospheric study because of the brightness of their star,” says Michelle Kunimoto, a postdoc in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research and one of the discovery’s lead scientists. “Is there a volatile-rich atmosphere around these planets? And are there signs of water or carbon-based species? These planets are fantastic test beds for those explorations.”

The team will present its discovery on June 15, 2022, at the meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Pasadena, California. Team members at MIT include Katharine Hesse, George Ricker, Sara Seager, Avi Shporer, Roland Vanderspek, and Joel Villaseñor, along with collaborators from institutions around the world.

Illustration of NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) at work. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Data power

The new planetary system was initially identified by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), an MIT-led mission that is designed to observe the nearest and brightest stars, and detect periodic dips in light that could signal a passing planet.

In October 2021, Kunimoto, a member of MIT’s TESS science team, was monitoring the satellite’s incoming data when she noticed a pair of periodic dips in starlight, or transits, from the star HD 260655.

She ran the detections through the mission’s science inspection pipeline, and the signals were soon classified as two TESS Objects of Interest, or TOIs — objects that are flagged as potential planets. The same signals were also found independently by the Science Processing Operations Center (SPOC), the official TESS planet search pipeline based at NASA Ames. Scientists typically plan to follow up with other telescopes to confirm that the objects are indeed planets.

The process of classifying and subsequently confirming new planets can often take several years. For HD 260655, that process was shortened significantly with the help of archival data.

Soon after Kunimoto identified the two potential planets around HD 260655, Shporer looked to see whether the star was observed previously by other telescopes. As luck would have it, HD 260655 was listed in a survey of stars taken by the High Resolution Echelle Spectrometer (HIRES), an instrument that operates as part of the Keck Observatory in Hawaii. HIRES had been monitoring the star, along with a host of other stars, since 1998, and the researchers were able to access the survey’s publicly available data.

HD 260655 was also listed as part of another independent survey by CARMENES, an instrument that operates as part of the Calar Alto Observatory in Spain. As these data were private, the team reached out to members of both HIRES and CARMENES with the goal of combining their data power.

“These negotiations are sometimes quite delicate,” Shporer notes. “Luckily, the teams agreed to work together. This human interaction is almost as important in getting the data [as the actual observations]. “

trazione planetaria

In definitiva, questo sforzo di collaborazione ha rapidamente confermato la presenza di due pianeti intorno a HD 260655 in circa sei mesi.

Per confermare che i segnali di TESS provenissero effettivamente da due pianeti in orbita, i ricercatori hanno esaminato i dati sia di HIRES che di CARMENES della stella. Entrambe le indagini misurano l’oscillazione gravitazionale di una stella, nota anche come velocità radiale.

“Ogni pianeta in orbita attorno a una stella avrà una piccola forza gravitazionale sulla sua stella”, spiega Kunimoto. “Quello che stiamo cercando è qualsiasi leggero movimento di quella stella che potrebbe indicare un oggetto di massa planetaria che la sta attirando”.

Da entrambi i set di dati d’archivio, i ricercatori hanno trovato segnali statisticamente significativi che i segnali rilevati da TESS erano effettivamente due pianeti in orbita.

“Poi abbiamo capito di avere qualcosa di molto eccitante”, dice Sporer.

Il team ha quindi esaminato da vicino i dati TESS per determinare le caratteristiche di entrambi i pianeti, compreso il loro periodo orbitale e le dimensioni. Hanno determinato che il pianeta interno, soprannominato HD 260655b, orbita attorno alla stella ogni 2,8 giorni ed è circa 1,2 volte più grande della Terra. Il secondo esopianeta, HD 260655c, ruota ogni 5,7 giorni ed è 1,5 volte più massiccio della Terra.

Dai dati sulla velocità radiale di HIRES e CARMENES, i ricercatori sono stati in grado di calcolare la massa dei pianeti, che è direttamente correlata all’ampiezza con cui ogni pianeta trascina la sua stella. Hanno scoperto che il pianeta interno ha una massa due volte la massa della Terra, mentre il pianeta esterno ha una massa di circa tre masse terrestri. Dalle sue dimensioni e massa, il team ha stimato la densità di ciascun pianeta. Il pianeta interno più piccolo è leggermente più denso della Terra, mentre il pianeta esterno più grande è leggermente meno denso. È probabile che entrambi i pianeti, a seconda della loro densità, siano di composizione terrestre o rocciosa.

I ricercatori stimano anche, sulla base delle loro orbite brevi, che la superficie interna del pianeta abbia una tostatura di 710 K (818 gradi).[{” attribute=””>Fahrenheit), while the outer planet is around 560 °K (548 °F).

“We consider that range outside the habitable zone, too hot for liquid water to exist on the surface,” Kunimoto says.

“But there might be more planets in the system,” Shporer adds. “There are many multiplanet systems hosting five or six planets, especially around small stars like this one. Hopefully, we will find more, and one might be in the habitable zone. That’s optimistic thinking.”

This research was supported, in part, by NASA, the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft, the Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad, and the European Regional Development Fund.

“Sottilmente affascinante social mediaholic. Pioniere della musica. Amante di Twitter. Ninja zombie. Nerd del caffè.”