Gli astronomi guidati dalla Durham University hanno scoperto uno dei più grandi buchi neri mai scoperti, con una massa di oltre 30 miliardi di volte quella del Sole, attraverso l’uso di lenti gravitazionali e simulazioni di supercomputer presso la struttura DiRAC HPC. Questa rivoluzionaria tecnologia, che simula il viaggio della luce attraverso l’universo, ha permesso ai ricercatori di prevedere con precisione il percorso della luce come si vede nelle vere immagini del telescopio spaziale Hubble. La scoperta è stata pubblicata in Avvisi mensili della Royal Astronomical Society.

Un team di astronomi ha scoperto uno dei più grandi buchi neri mai scoperti, sfruttando un fenomeno chiamato gravitational lensing.

Gravità curvilinea della luce

Il team, guidato dalla Durham University nel Regno Unito, ha utilizzato la lente gravitazionale – in cui una galassia in primo piano si piega e ingrandisce la luce proveniente da un oggetto distante – e le simulazioni al supercomputer presso la struttura DiRAC HPC hanno permesso al team di esaminare da vicino come la luce viene deviata da un buco nero all’interno di una galassia a centinaia di chilometri di distanza, a milioni di anni luce dalla Terra.

Il team ha simulato la luce che viaggia attraverso l’universo centinaia di migliaia di volte, con ogni simulazione che coinvolge una massa diversa[{” attribute=””>black hole, changing light’s journey to Earth.

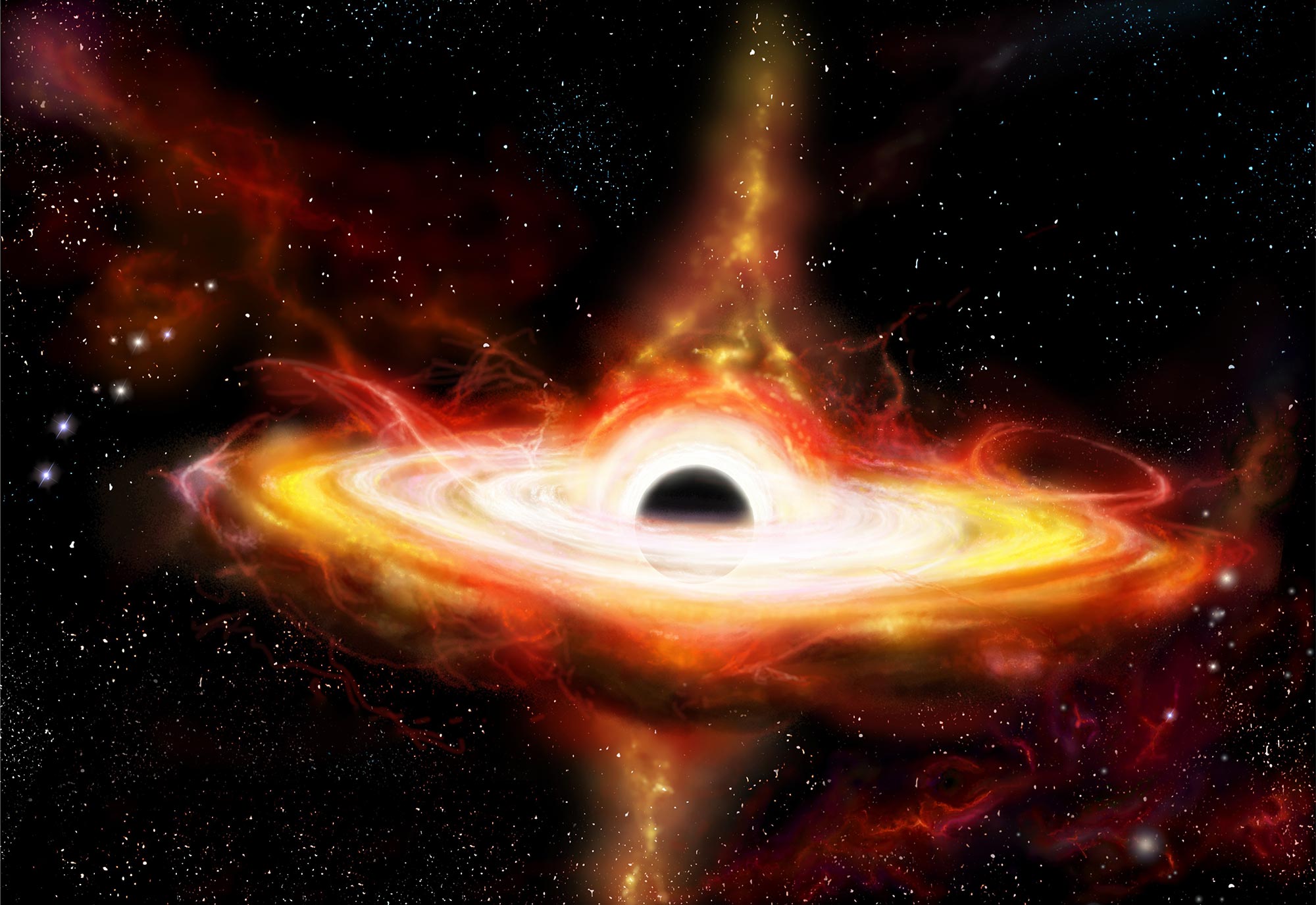

An artist’s impression of a black hole, where the black hole’s intense gravitational field distorts the space around it. This warps images of background light, lined up almost directly behind it, into distinct circular rings. This gravitational “lensing” effect offers an observation method to infer the presence of black holes and measure their mass, based on how significant the light bending is. The Hubble Space Telescope targets distant galaxies whose light passes very close to the centers of intervening fore-ground galaxies, which are expected to host supermassive black holes over a billion times the mass of the sun. Credit: ESA/Hubble, Digitized Sky Survey, Nick Risinger (skysurvey.org), N. Bartmann

30 billion times the mass of our Sun

When the researchers included an ultramassive black hole in one of their simulations, the path taken by the light from the faraway galaxy to reach Earth matched the path seen in real images captured by the Hubble Space Telescope.

What the team had found was an ultramassive black hole, an object over 30 billion times the mass of our Sun, in the foreground galaxy – a scale rarely seen by astronomers.

This is the first black hole found using gravitational lensing and the findings were published today (March 29) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Un video che mostra come gli astronomi hanno utilizzato la lente gravitazionale per scoprire un buco nero 30 miliardi di volte la massa del Sole in una galassia a 2 miliardi di anni luce di distanza. Credito: Università di Durham

Guardando indietro nel tempo cosmico

La maggior parte dei più grandi buchi neri che conosciamo sono in uno stato attivo, poiché la materia che viene trascinata vicino al buco nero si riscalda e rilascia energia sotto forma di luce, raggi X e altre radiazioni.

Il lensing gravitazionale consente di studiare i buchi neri inattivi, cosa che attualmente non è possibile nelle galassie lontane. Questo approccio potrebbe consentire agli astronomi di rilevare buchi neri inattivi che sono più massicci di quanto si pensasse in precedenza e indagare su come diventano così massicci.

La storia di questa stessa scoperta è iniziata nel 2004, quando il collega astronomo della Durham University, il professor Alastair Edge, ha notato un arco gigante di una lente gravitazionale durante la revisione delle immagini SGS.

Avanti veloce di 19 anni e con l’aiuto di alcune foto ad altissima risoluzione di[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Hubble telescope and the DiRAC COSMA8 supercomputer facilities at Durham University, Dr. Nightingale and his team were able to revisit this and explore it further.

Exploring the mysteries of black holes

The team hopes that this is the first step in enabling a deeper exploration of the mysteries of black holes, and that future large-scale telescopes will help astronomers study even more distant black holes to learn more about their size and scale.

Reference: “Abell 1201: detection of an ultramassive black hole in a strong gravitational lens” by J W Nightingale, Russell J Smith, Qiuhan He, Conor M O’Riordan, Jacob A Kegerreis, Aristeidis Amvrosiadis, Alastair C Edge, Amy Etherington, Richard G Hayes, Ash Kelly, John R Lucey and Richard J Massey, 29 March 2023, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stad587

The research was supported by the UK Space Agency, the Royal Society, the Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC), part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and the European Research Council.

This work used both the DiRAC Data Intensive Service (CSD3) and the DiRAC Memory Intensive Service (COSMA8), hosted by University of Cambridge and Durham University on behalf of the DiRAC High-Performance Computing facility.

“Sottilmente affascinante social mediaholic. Pioniere della musica. Amante di Twitter. Ninja zombie. Nerd del caffè.”